RECORD Magazine - 09/1983

Interviewer: John Hutchinson – Record, September 1983

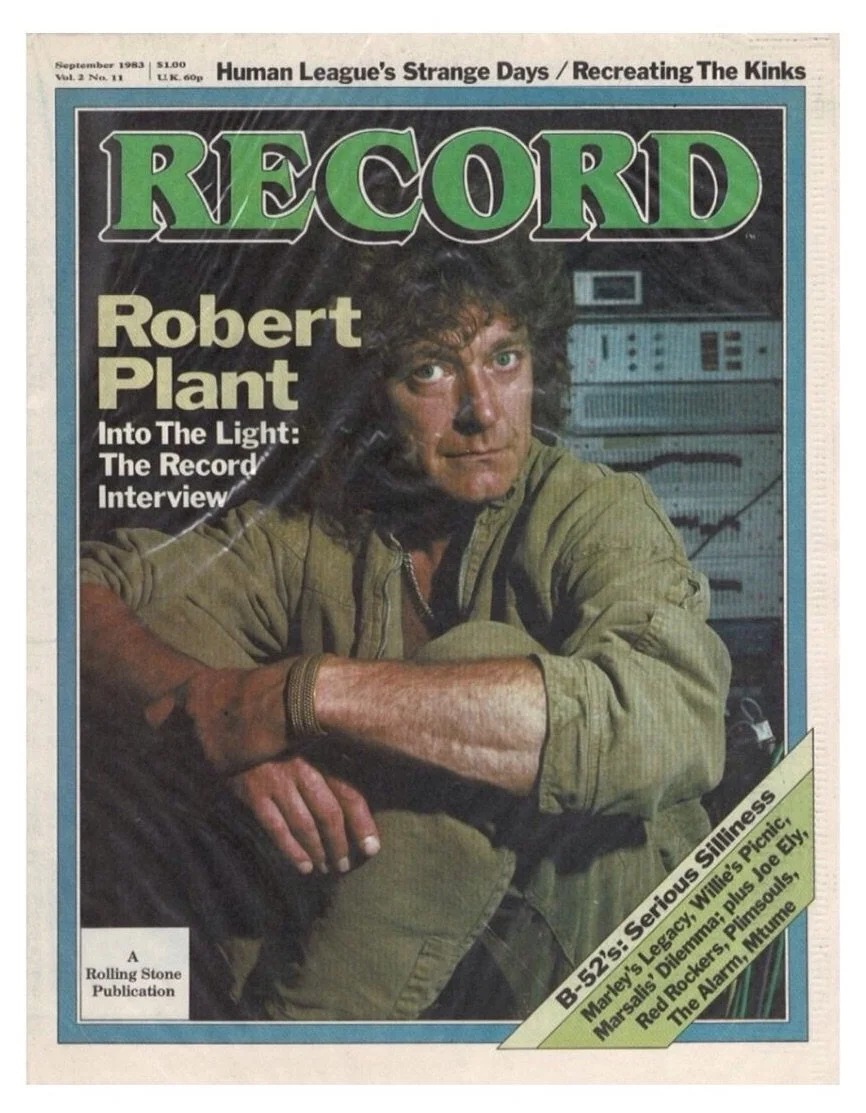

Plant: Into The Light

Led Zeppelin now a fond but distant memory, Robert Plant turns his attention towards a new solo album, a new band and a world tour – all part of a mission, he says, “to exude an air of positivity rather than one of darkness and pondering.”

IN LATE 1968 Led Zeppelin released its first album, and contained in the grooves were early signs of the unease that was beginning to undermine a generation’s idealism. From the very outset the band blended over-the-top blues dramatics with songs of quiet sensitivity; their music ran through a gamut of pace changes and dynamics. What’s more, the nervous bravado of Jimmy Page’s guitar coupled to Robert Plant’s intense, high-pitched singing seemed to have a visceral effect on many people who had been too young to be part of the hippie movement, but who shared the counterculture’s aims and aspirations. Even if their elder brothers and sisters were growing weary and disillusioned,16- and 17-year-olds were determined to have some more fun. Led Zeppelin was their band. Combining dreams with foreboding, bombast with reflection, and, above all, projecting their feelings with delirious fervor, Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones, and John Bonham constituted what was the world’s most popular rock act.

On December 4th,1980, two months after John “Bonzo” Bonham’s unexpected death, Led Zeppelin announced their breakup. Zeppelin fans had speculated endlessly about who might be drafted in as a substitute, but in vain. The three remaining members believed that Bonham was irreplaceable, and rather than limp along without him, they decided to call it a day. The end of Led Zeppelin had a profound impact on Robert Plant. He had been friendly with Bonham for years, and it was he who had put forward Bonzo’s name to Jimmy Page as a suitable drummer for the group – they had played together in the Birmingham-based Band of Joy. Bonham’s death was a personal loss, and probably served to remind Plant further of the transience of life, because it was only three years earlier that he had lost his young son through illness. Besides the distress Bonham’s death caused Plant, the band’s demise left him musically adrift. Led Zeppelin had always been a tightly knit group, its members seldom straying far beyond the confines of their joint activities, so after twelve years of musical introversion, Plant found himself having to face up to the challenge of starting over, without the benefit of support from his friends. And, as he is quick to point out, he was a singer, not an instrumentalist.

As Plant describes it, the task before him was imposing, but less than two years later his first solo album, Pictures at Eleven, was moving rapidly up the charts. Though he was encouraged by the record’s sales (it reached number three in the States and number two in Britain), and by its critical reception, Plant was particularly delighted with his own personal achievement in bringing the project to fruition. Almost immediately he began work on a second album, The Principle of Moments,which has just been released on his own new label, Es Paranza, distributed in the States by Atlantic. On June 7th I met Plant in a London hotel. It wasn’t difficult to spot him there, because among the brisk, neatly suited businessmen who passed to and fro in the marbled foyer, Robert Plant was something of an outsider. He is almost 35, tall, well built, and lightly tanned; on that occasion he was wearing a faded black jumpsuit, with white espadrilles on his bare feet. He looked as though he would be more at home on a Greek island than in the bustle of urban London. Plant is a gentle and courteous man, who acts with firm composure. He’s extroverted, but you can see that life has mellowed him, and there is a fundamental seriousness in his character that regularly comes to the surface in conversation. He’s humorous, but he is also a private person.

I was talking to a drummer friend of mine recently and we both agreed that the only reason why he and I are really going for it now is because we possess the quality that a lot of people tend to lose, either out of choice or out of neglect, and that is “keenness.” It’s a really corny word, but it’s apt. And it seems great that, providing you are good at what you do, you can draw in people from all over the place and do anything – anything at all.

Do you have much company pressure regarding what you do? No. There was never any pressure on Zeppelin, so there should never be any pressure on me. I’m the artist, and if I don’t want to go out on tour, or feel uncomfortable about doing so, there’s absolutely no pressure that they can exert on me – or anybody, for that matter. You make your own rules, and you should only go where you want to go. Who wags the dog’s tail, after all? I really believe the artist can’t just turn it on if the well’s dry. You can only turn it on when the soul is so full that it’s just going to pour out. I think you’ll find that on the new album there are some dramatic moments that are strange, and maybe a little uncomfortable for the listener, but at the same time they transfix you. You see, although people say that I’ve got a good voice, and that I express myself well, they also say that I’ve been something of a “hero.” But I don’t play any roles, and I don’t really care who wants what – the only time it’s worth giving is when you’re full of feeling and you can’t suppress it any longer. Then you might manage to induce the same emotion in people around you.

You must find it very different from working with Zeppelin, when you could share responsibility with the others. Now the buck stops with you. Yeah. If Jimmy and I had disagreements we would curse each other to everyone else, but be very polite to one another. We knew what we were talking about, because we were very close. With these new people it’s extremely difficult, especially because my track record is a little daunting for anyone who is going to step into the situation with me. The fact that Pictures at Eleven actually exists at all is a major milestone in my life – I fought to put it out when I did because I couldn’t sit on it any longer. It was very respectable in the way it was received rather than in the way it sold: whatever commercial success it had was greatly outweighed by the fact that it was reviewed seriously. I imagine that a lot of critics approached it with the attitude of “Oh, here we go, here are the death throes of another hero of the Sixties and Seventies,” so it was wonderful to see that people actually listened to it and analyzed it, rather than just wrote it off.

The last time we met you said your new album, The Principle of Moments, was going to be quite different from Pictures at Eleven. How do you feel about it now that it’s done? It’s a departure. On this album there has been a distinct effort – no, effort is the wrong word – there’s been a movement towards the creation of more space and light within the whole thing. There is still a lot of intensity, but the delivery is different. Also, strangely enough, there are more tunes for tunes’ sake. I used the same band and we recorded it in stages again: like the last time, we used two drummers, Phil Collins and a guy called Barriemore Barlow (former Jethro Tull drummer). The two tracks that Barry played on are very stark, so for me and for the people who are accustomed to listening to what I do, they add a really pleasing alternative to conventional drumming. I would say that it is probably, and pleasantly, the most fragmented piece of work I’ve had anything to do with since Physical Graffiti. For that reason, if anyone were to analyze the emotion in it, or its musical direction, there is nothing they can get a grip on. And that’s very healthy. On one track one person’s influence might be stronger, and on another somebody else’s, so the album swings from one intention to the other. I’ve had a part in everything, though, and in that way it’s getting easier and easier.

How long are you going to tour? I would think that there’s a distinct possibility I’ll tour for at least a year. The musicians themselves have become far more comfortable and at ease with the situation. Usually when you talk to a journalist you can smooth over any rough edges by saying, “Yeah, it’s coming along nicely,” and all the rest of the bullshit that goes with it, but I don’t need to do that. It actually has gelled now, and in every respect we are a working unit. We’re playing together every day. We finished recording the album in the middle of May, and I took a little time off because I think the studio had got to me a bit. Because of our intention to make the album different, we took great pains to make sure we didn’t overdo anything. It’s harder to understate than to flood a track; when you try to take everything away and just leave the bare essentials and the occasional dynamic effect, it can take that much longer.

Has working with new musicians changed your style at all, or are you very much the dominant musical personality? Sometimes it changes a bit. I’m only dominant when I don’t like what’s going on.

Who have you been listening to recently that might have influenced your music? No one consciously. I listen to Gustav Mahler occasionally; Ry Cooder, the Beat – I go from one extreme to another. I’ve also been listening to the Cocteau Twins: they’re very spacey, like a modern-day version of Kaleidoscope. Incidentally, it seems as if a lot of music has gone right ’round and is knocking at the door of Clear Light and bands like that. I was talking to Echo and the Bunnymen the other day, and from what they were saying it appears that there is a resurgence of interest in all that sort of early psychedelia.

I know you used to listen to folk music, to groups like the Incredible String Band. Were you influenced at all by their vocal style? I always admired Mike Heron and Robin Williamson’s vocal approach, just as I liked Dave Swarbrick (of Fairport Convention) and Richard Thompson. That kind of Eastern European folk intonation is beautiful – I don’t think I can do it, but it is very lovely. If I manage occasionally to touch it for a second, then that’s all well and good, and I’m pleased to know I listened to the music closely enough to hit it just like that. It’s not easy, especially because I have a vocal style that isn’t very changeable – or rather, which I have no wish to change. As long as everything underneath is moving all the time, then my voice should be the characteristic across the top.

Who did you listen to in the early days who influenced your singing style? I used to listen to what were, in England, the more obscure American hits – a lot of New Orleans rock, what you might call R&B for whites. It was mostly remarkable one-off records that set the whole imagination tingling. It was really “roots” music – the vocals were very plaintive. Although it wasn’t Robert Johnson or Blind Willie McTell, it was still very poignant, and had a remarkable effect on how I wanted to sing. I realized that immersing myself in country blues on a folk-club circuit was perhaps too well-mannered and predictable. There was just polite feedback coming from the audience. I wanted to get some balls, some shrieking, into my music, so that took me vocally more into the guttural American approach to singing, which I suppose people like myself, Robert Palmer to an extent, and definitely Lennon and McCartney got into. We all had a kind of edge on our voices which comes from American R&B. Steve Stills had that kind of voice too, as he had been tuning into that kind of stuff, as had Ry Cooder. We’re all from the same school.

Since we’re talking about influences, I’d like to ask if Jimmy Page’s interest in the occult was really serious? I don’t think that Jimmy was particularly interested in the occult, but only in Aleister Crowley, as a great British eccentric. All eccentrics are interesting, but Crowley was a very clever man. Jimmy had an innocent interest in him, just as many people have fixations on individuals at one level or another.

I seem to remember reading that you blamed his dabbling in the occult for some tragic events in your life. No, that’s bullshit. I never said that; it’s absolute poppycock. It wouldn’t have made any difference who listened to one thing, or who did another. You can be anything, or do anything, and you don’t have to affect your friends by what you do. At least not in your leanings and desires.

In retrospect, how do you assess your contribution to Led Zeppelin? Zeppelin is still very wonderful and always will be. The tension in some of the tracks can’t be touched by what I’m doing now. It’s far superior in many respects – not in the quality of the music, but in the amazing moments. There are times of magic on every record.]

What were the highlights? Things like ‘The Wanton Song’. I remember recording it, the whole session – it was so electric, so quick and so fruitful. ‘Trampled Underfoot’ was another one. The more impromptu numbers are the ones that really come to mind, rather than the time-consuming things that were worked out and constructed.

In a previous interview you told me that your singing in Led Zeppelin was a form of “counterwork” with Jimmy Page. Exactly how did the two of you work out your parts? There were so many elongated and free form guitar sections, and at certain points in the proceedings there were anchor points, like junctions, which I knew were coming. Maybe four bars beforehand there would be a musical signal, and after a while I felt the natural need to express myself at the same time, so at these signals we developed instrumentally and vocally into the next pattern. I’d been listening to scat singing along the way, and maybe that was in the back of my mind. But the more flowing, searing notes that were shared between guitar and voice were very eerie and dramatic – and a hell of a risk too, because whenever it happened they were usually pretty high notes. I couldn’t do it today, that’s for sure – not right now, anyway! The fact that I didn’t stop singing when the lyrics finished became one of my trademarks.

Besides the emphasis on the bottom end, there was a good deal of echo and reverb in Zeppelin productions. Was that the key to the band’s “big” sound? I suppose what you say is correct, but the combinations are infinite, really. The echo and the use of the voice in that style also made the music spacey and ethereal.

You didn’t use quite as much echo on Pictures At Eleven. Not in that way, no. But I’m sure that if I hit the road again I’ve got to throw it in because I enjoy it and it’s me. It’s nice to be able to play against the echo: you can get multiple vocal things going by just phrasing the voice at the right time, hitting a note, letting the echo do its bit and then compounding harmonizing with yourself until you’ve got a block of sound. I can get 32 voices in a matter of 15 seconds through that sort of compounding. Just to have something in the middle of nowhere taking off like that…

What would you regard as your major triumphs? And at what points in your life have you felt most fulfilled? I felt most fulfilled upon the arrival of my children, because they don’t really change. Obviously they have their own changes, but our relationship doesn’t alter that much. Everything else has its fluctuations. I suppose I would have fluctuations with my kids too if I weren’t a reasonable father to them. Besides that, I can’t recall any particular triumphs, other than the fact that I’ve got very close to touching base a couple of times with some of Zeppelin’s early success, and coming out of one or two situations when I thought “This is it… no more,” then picking myself up and starting again. To that extent Pictures At Eleven will always remain a major part of my life, symbolically, if nothing else. One thing about being a member of a very close-knit family is that you can never ever imagine you’re going to be without them; so when you have to re-evaluate your position and what it takes to make you function as a reasonable human being, you find that one of the most important things is to express yourself with whatever the gods have given you. Then you ask yourself, how on earth do I begin? You have to take it from the point where you realize that you do have to start, rather than sit around in the stately home or wherever, and get to the position where there is a piece of vinyl in front of you. The fact that people buy it is secondary – it sounds easy to say that, but I’ve had to go from fourteen years of insulation, away from everybody, pick my way through everything, and come up with a record that some people actually enjoy. Every step of the way was an experiment, dealing with each individual, dealing with the moments of frustration.

Being one of heavy metal’s elder statesmen, how do you feel about the bands that have sprung up in the years since Zeppelin’s formation? Zeppelin emerged from the embers of the Yardbirds, and had all sorts of influences, such as blues and west coast American music. We had a certain ability to extend our music, which gave it drama, dynamics, emotion, and space. At one moment it could be Wagnerian, and at the next like Eddie Cochran. That was “heavy,” in the sense that it was sometimes a little hard to take, not because it was a mass of uncontrolled crescendo’s. And now, the remnants of that era’s imitators – and there are only imitators left, or tired exponents from the first time ’round who are still flogging it – have all lost their way. The subtlety that was in Led Zeppelin was never shared by much of the music that was around – Blue Cheer was as “heavy metal” as Iron Maiden. I’m afraid it’s all become very professional, as in Def Leppard and people like that – just pretty songs with the odd scream, and a guitarist who leans back and bursts into a great flurry of notes. Whatever was there in 1969 and 1970 has become diluted or lost in translation.

Did you ever feel a sense of responsibility as, in your words, a “hero”? Only to exude an air of positivity, rather than one of pondering and darkness. At the time even the symbolic actions of guys like Alice Cooper made me a little sick, because I thought there was not enough light – there never is.

Apart from Zeppelin you’ve kept a fairly low profile. But I understand now that you’re getting ready to close up your farm and move to London. Why the change? I think I could do with a few years of total immersion in music and stage, and a whole change of stimuli: I’d like to get dug in to the next few years in every respect. I’ll always keep at least a toe in the country, but maybe there is peace in the city – actually I think it’s possible to find peace anywhere if you’ve got the right state of mind. The way I am now, I feel very content artistically, barring my musical frustrations. Beyond that, it’s all settling down. I do take my drives in the country, and do the things I’ve always done, but really I haven’t a great deal of time. What time I have I spend playing tennis: it’s a great leveler after hours and hours of concentration.

Do you feel you have peace of mind now? I don’t know. Because I’m a singer and not a musician there’s always a level of frustration that I carry with me – there’s a lot of emotion that I can’t express, which I have up there in my head. But I feel I have as much peace as I’ve ever had, which is a fair smattering, really.

What would you like to have been if you hadn’t been a singer? A whore! No, maybe a forester, or one of those nineteenth century botanists who went abroad and gathered incredible species of plants from China, Japan or wherever. Some kind of traveler, perhaps, at the turn of the century, or even as late as the ’30s. A while ago I was reading books by Peter Fleming and Bruce Chatwin, and found that being a foreign correspondent for a major newspaper seems to give you carte blanche to take six months and the right calling-cards and travel from Cathay to Kashmir. I’d like to have had the eloquence and skill to write down the escapades, as well as the breeding and the ways of the gentle so I could handle all the different situations. The idea of that kind of exploration, where you don’t have to be a geologist or an exceptionally daring character, appeals to me very much.

Any regrets musically? No. I don’t think I’ve ever had any regrets, musically, about anything I’ve ever done. With Zeppelin it was so homey and comfortable that I never even had a thought beyond the record or tour we were involved in – I was totally consumed by it. I suppose that socially it might have been better for me to have met more people earlier on, but I’ve got plenty of time to catch up.