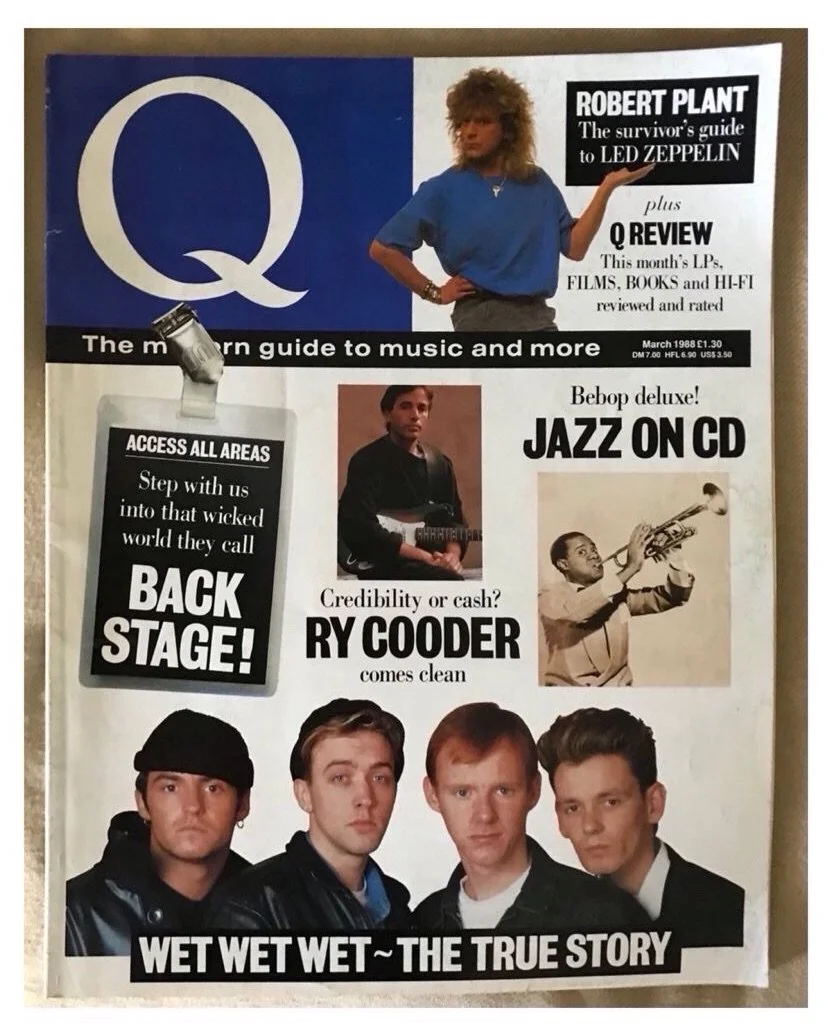

Q Magazine - 03/1988

Interviewer: Tom Hibbert – Q, March 1988

“I CAN’T BLAME anybody for hating Led Zeppelin. If you absolutely hated ‘Stairway To Heaven’, nobody can blame you for that because it was, um…so pompous.”

Robert Plant, the one-time writhing and mewling Adonis-figure who did the singing and the shrieking for the most monstrous, most celebrated, most infamous hard rock act of all times, leans back in the plump sofa in the offices of his new manager Bill Curbishley (who managed The Who) and enters confession. The famous locks that once shook in the spots of the grandest stadiums on earth are just near shoulder-length now – respectable; the face is lined with the sins of the ages but alive and amicable. Robert Plant owns up: “Those accusations that were leveled at Zeppelin at the end, during punk, those accusations of remoteness, of playing blind, of having no idea about people or circumstances or reality, of having no idea about what we were talking about or what we were feeling, of being deep and meaningless and having vapid thoughts – there was a lot of substance in what was being said. People were quite right to say all that. It hurt at the time but I’d have to plead guilty.”

Robert Plant pleads guilty. He is only now coming to terms with his history, becoming able to sort the Good Times from the Bad. Led Zeppelin at their best is something he’ll always be proud of. At their worst, most self-indulgent? Well… On the wall some feet away, there’s a poster of Judas Priest. Plant springs to his feet, strides purposefully towards it and points a scornful finger at this gargantuan photo of the heavy metal chaps dressed in their leather and their chains, and festooned, naturally, with sundry Diabolic tokens. “If I’m responsible for this in any way (which, of course, he is – the influence of Led Zeppelin on heavy metal can never be overestimated), then I am really, really embarrassed. It’s so orderly and preconceived and bleuurghh. Hard rock, heavy metal these days is just saying ‘Come and buy me. I’m in league with the Devil – but only in this picture because after that I’m going to be quite nice and one day I’m going to grow up and be the manager of a pop group’, or whatever. Zeppelin was never saying that. When I see something like this (the finger wags sternly like some demonstrative prosecuting counsel at a murderous defendant), it’s then that I wish I could materialize Page at my side. And the two of us would steam up on stage and take their names for being absurd. It’s like a bunch of Arabian eunuchs – there’s no balls. We’d have them reported to a higher authority for taking the good name of Zeppelin in vain. Zeppelin, for all their mistakes and wicked ways, were bigger and greater than any of that kind of nonsense…”

ROBERT PLANT HAS spent seven years – since the death of John ‘Bonzo’ Bonham and the demise of the group – attempting to lay the ghost of Led Zeppelin. His four solo LPs to date – Pictures At Eleven (1982), Principle Of Moments (1983), Shaken ‘n’ Stirred (1985) and the new Now And Zen – have hinted but fleetingly at the black sound and fury of old – this new music is polished and relatively modern, with proper choruses to prove it. In his (few) interviews he has mentioned that band sparingly, only in passing, preferring to discuss current projects and musical preoccupations (“I hate pop. In a fair world Let’s Active should be Number 1, R.E.M. should be Number 2 and I should be in there somewhere behind them at Number 5…”) He has stripped those horny squealings of old from the vocal repertoire and ironed the voice into a more round and orthodox rock ‘n’ roll implement. He has had annual telephone calls from John Paul Jones (whom he never sees) suggesting that Led Zeppelin reform (“Jonesy always was a breadhead”), and he has treated these with contempt – Live Aid, at which Page, Jones and Plant were reunited for 14 minutes (we’ll come to that later) was most definitely a one-off. And he has always steadfastly ignored, when on stage with his own band, the constant cries of the audience for Percy – as Planty as known to his friends and admirers – to do a ‘Stairway To Heaven’ or a ‘Whole Lotta Love’ or a ‘Dazed And Confused’ or a… (“Where’s Jimmy? That’s what they always shout. Where’s Jimmy? In fact, that should have been the name of the new album: Where’s Jimmy?”). A sturdy refusal to comply with audience’s nostalgic wishes – until, that is, last night, when, at a secret gig in Folkestone to test Now And Zen‘s material with his new young band (billed as The Band Of Joy, Plant and Bonham’s Midlands group of 1967/8 whose set was full of songs by Moby Grape, Jefferson Airplane and other West Coast entities) he encored with ‘Misty Mountain Hop’ (from Led Zeppelin’s untitled fourth album, the one with the Zoso “runes”) and found himself “up there, eating my words furiously”. The Zeppelin Beast (the number of which may or may not have been 666) is finally slaughtered and buried as far as Plant is concerned. Jimmy Page makes a Zeppelin-like guest appearance on Now And Zen and, finally, Robert Plant feels himself able to discuss those old and spooky days. He can talk about it now.

He can talk about how hard he found it to make the decision to leave all thoughts of Zeppelin behind and re-invent himself as a modern rock item after the (fatal) collapse of stout party Bonham in September 1980: “It was a very hard and difficult process to re-evaluate myself after that. I did nothing for as long as was respectful to Bonzo, really. Because he and I were best mates. Page and Jones obviously became friends but they were never mates like Bonzo was because we’d started out with that age and experience gap that was never totally bridged. But Bonzo and me were so close that all the kind of insinuations of carrying on and all that were just totally unacceptable to me. “Because I knew how much Bonzo loved what he did and I thought it would be terrible to just fob the whole thing off and say, Well, that’s it. We’d better get someone else now so that we can carry on this incredible sort of amoebic carnage game, you know. So rather than take the whole Zeppelin thing and try and do it myself, I rejected the whole thing. Anything to do with the enormity of the success and the attraction and the oddness of Led Zeppelin, I didn’t want to have anything to do with. So I cut my hair off and I never played or listened to a Zeppelin record for two years. It would have been longer but my daughter’s boyfriend who was in a psychobilly band started telling me that part of ‘Black Dog’ (from the “runes” album) was a mistake because there’s a bar of 5/4 in the middle of some 4/4. Well, my dander was up at that so I pulled the record out and plonked it on and said, Listen you little runt, that’s no mistake, that’s what we were good at! And having done that, I listened to the whole record and got really drunk and went, Right! I knew what I wanted to do. Not Zeppelin but I still wanted to sing. I knew I had to carry on because I love what I do. I love to be anxious and I love to nurture this thing like some kind of new woman every two or three years…”

He can talk about how hard he found it to approach the notion of assembling a band of his own: “We had always led a very cloistered existence in Zeppelin. We really didn’t know anybody else. We knew each other and we knew the entourage but that was about it. And a lot of people were very frightened of us and avoided us like the plague. It was only the Stones that we really ever had anything to do with because we used to take the piss out of everybody else. So it was hard for me getting to know other musicians for the first time. But once I’d met some – people like Phil Collins (who played drums on Plant’s first two LPs) – it was good because I could see them thinking, Oh, he’s not so frightening. He’s quite dumb but he’s not frightening. And I’d go back and see Jimmy now and again and I’d try and say, Now, come on. It’s quite nice out there, you know. And so he started stepping out as well, leaving his great shell at home. It was like the metamorphosis; he’d step out a bit and then go home and climb back into his shell and the shell would grow. It’s like Kafka. Kafka could have been writing about Page. He’s still Jimmy Page, you see. I’m sure he’s still got dragons on his jeans. And if he hasn’t got them on his jeans, they’re on his skin by now…”

He can talk about how hard it was, after 14 years in a songwriting partnership with Jimmy Page, to start writing with someone else (guitarist Robbie Blunt): “It was so uncomfortable to begin with that I wasn’t sure I could handle it. Because Page and I had known each other back to front in that area. We had had a rather self-congratulatory partnership for years and it had been comfortable – a bit twitchy at times because of all the drugs but basically comfortable. And so to start with anyone else was a very, very odd feeling. Unnerving. Because I started getting so many flashbacks of the night Page and I wrote bits of ‘Stairway To Heaven’ or of doing the lyrics of ‘Trampled Underfoot’ or whatever. I found myself getting all these great swirls out of the mist and at first I couldn’t cope. But I got used to it. And once I’d done it once, I realized I could do it a million times…” AND ROBERT PLANT can even talk about Hammer Of The Gods, Stephen Davis’s unauthorized Led Zeppelin biography, published in 1985, that told us things we’d suspected for years – tales of grand debauchery, of Page cavorting naked on tea trolleys before roomfuls of groupies, of Bonham’s bottle binges that would end in near rape, of the girl in the hotel room being made “love” to by a red snapper fish, about the aggressive, gangster-like tendencies of manager Peter Grant, and more, much more.

“Hammer Of The Gods. Well there was some truth” – (the snapper episode, it seems, really did happen, though Plant was not a party to it, nor to any of the other grosser outrages in the tale) – “and a tiny bit of insight in that book. But, basically, it was compilation of Richard Cole’s clearer moments of recollection in between smack and God knows what else.” (Cole was Zeppelin’s tour manager and lieutenant to Grant; or sergeant – “Cole was the ultimate sergeant – big, nasty, a natural leader, an Anglo-Irish pirate who would have been at home with the notorious White Companies, looting France during the Hundred Years War” runs Davis’s descriptive introductory passage on the man.) “But a lot of what he remembered about Zeppelin wasn’t about Zeppelin at all. I think a lot of his recollections were confused with memories from when he was with Vanilla Fudge or the Young Rascals or Hendrix. Of course, Zeppelin had many moments of outrage too sordid to mention but somebody else would write a better book, I think. A funnier book, because 90 per cent of what we got up to was just funny. Richard just possesses an inherent bitterness because he was in a constant position of absorbing and reflecting glory without ever being given the reins of authority because he was always second in command to Peter Grant. So when it all ended he decided to get his own back on a bunch of guys who were just shambling their way through the universe. It’s sad, in a way, because underneath all that fighting and kicking and wrecking, he’s a really nice man…” Cole doesn’t come across as a “nice man” in the Stephen Davis book. He comes across more as an unsavory leech, an opportunist and a pervert. Peter Grant, meanwhile, comes across as a gangster and a monster. Either the book lies or Plant has a forgiving/ naive/diplomatic nature. He still loves Grant, this man who, all evidence tells us, was not averse to beating a man unconscious if his path were crossed, however innocently.

“You have to understand the kind of man Peter Grant was…is,” says Plant. “An ex-wrestler who’d have been on the road with Wee Willie Harris and Gene Vincent in the bad old days. He had his own way of getting things done. Since Zeppelin…well, I have no idea what’s happened to him. But he’s the man who should write the book. He maneuvered Richard Cole into every circumstance going and if we were The Gods, Grant was The Hammer. And Grant was the one who kept us cloistered from the world. Well, that’s not quite true. I still knew how to use money, how to shop and how to drive, how to shit and walk, I still saw my family and I still spoke to the milkman, but we didn’t see too many people in our world – rock ‘n’ roll. We were kept remote. But what that book doesn’t tell you is that Peter Grant was one of the most witty and intelligent men. He smashed through so many of the remnants of the old regime of business in America. Like all the old road shows in America, which I was too young to have gone on, thank God: Page used to travel in a bus in The Yardbirds with Gary Puckett And The Union Gap and The Shirelles and Bobby Vinton and nobody got a cent apart from the promoter. Then we came along and Grant would say to promoters, Okay, you want these guys but we’re not taking what you say, we’ll tell you what we want and when you’re ready to discuss it you can call us. And of course, they would call us and do things on our terms, on Grant’s terms, because otherwise they’d be stuck with Iron Butterfly. Peter Grant changed the rules. He rewrote the book. And he did so much for us that in 1975 he had to turn around and say, ‘Look, there’s nothing else I can do for you guys. We’ve had performing pigs and high-wire acts, we’ve had mud sharks and all the wah, but there’s no more I can do. Because you really now can go to Saturn.’

“We had twitchy times at the end, me and Peter Grant, but I owe so much of my confidence and my pig-headedness to him because of the way he calmed and nurtured and pushed and cajoled all of us to make us what we were. There were so many times I wanted to wring his neck but I wish him well and I wish he’d get off his fat arse and do something because I happen to love him a lot. Funny chap…” Hammer Of The Gods suggests another charge, one well known to all fans of Led Zeppelin and to those who grew up with the myth and the legend of this peculiarly successful group. It is this: for fame and fortune, Led Zeppelin made a pact with Satan himself. Thus: play ‘Stairway To Heaven’ (the song that is still the most requested song on American FM radio; the song that still makes it into those listeners’ Top-Of-All-Time polls just behind 10cc’s ‘I’m Not In Love’ on Capital Radio and other stations) backwards and you will, it is said, hear a witchy, “twitchy” message in Beelzebub-styled code. “Here’s to my sweet Satan!” the tones of Lucifer proclaim. Or is it “I live for Satan!”? The Evangelists of America, who have spent many years searching for hell-fire and brimstone in the works of Led Zeppelin, are divided. But of one thing they (and many a gullible Zeppelin fan) are certain: Led Zeppelin dwelled within the bosom of the Prince Of Darkness. So where, pray, are Robert Plant’s spiky little horns?

“Oh, I cut those off with the hair, hahaha. No, all that crap came from Page collecting all the Crowley stuff. Page had a kind of fascination with the absurd, and Page could afford to invest in his fascination with the absurd, and that was it. But we decided years ago that it would be prudent to say nothing to people about all that because the people we’d have had to talk to were pretty lame. There was just no point in going along and bleating and saying, Listen, this is fucked, if you believe this Devil stuff, you’ll believe anything. So we just let it go. But it did infuriate. I mean, ‘Stairway To Heaven’, as much as I find it intolerable to even consider that song now, at the time it was important and it was something I was immensely proud of. Page and I had a moment when we wrote something incredibly pompous but at the time it was alright and the idea of the Moral Majority stomping around doingcircuit tours of American campuses and making money from saying that song is Satanist and preaching their bullshit infuriated me to hell. You can’t find anything if you play that song backwards. I know, because I’ve tried. There’s nothing there. In fact, I was thinking of putting some back-tracking on my last album saying ‘What did you miss from before? in Latin. It’s all crap, that Devil stuff, but the less you said to people, the more they’d speculate. The only way to let people know where you’re coming from is to talk to the press, and we never said fuck all to anybody. We never made a pact with the Devil. The only deal I think we ever made was with some of the girls’ High Schools in San Fernando Valley.”

SATAN’S FINEST PLAYED their last ever show on English soil at Knebworth in 1979 – two nights before 380,000 people. Plant remembers the occasion with mixed feelings. “The punks hated us for Knebworth, and quite rightly so. But we couldn’t go playing Nottingham Boat Club just to prove to people in long overcoats that we were OK. But although we were supposed to be the arch criminals and the real philanderers of debauchery and Sodomy and Gommorah-y, our feet were much more firmly on the ground than a lot of other people around. But you wouldn’t have believed that to see us swaggering about at Knebworth, because Knebworth was an enormous, incredible thing. I patrolled the grounds the night of the first gig – I went out with some people in a jeep – and people pushed the stone pillars down, with the metal gates attached, because they wanted to get in early. Those gates had been there since 1732 and they just pushed them over. It was a phenomenally powerful thing.” The following year Led Zeppelin toured Europe (a tour on which, Plant claims, the band showed they’d “learned a hell of a lot” from XTC and people like that. I was really keen to stop the self-importance and the guitar solos that lasted an hour. We cut everything down and we didn’t play any song for more than four and a half minutes.”) and on their return, John Bonham passed on, a surfeit of vodka in his belly, and Plant vowed that he’d never perform as part of Led Zeppelin again. Five years later and the promise he’d made himself was broken when, in Philadelphia, he and Page and Jones assembled on stage to play their 14 minutes – ‘Stairway To Heaven’ included – for Ethiopia. Mixed feelings here, too.

“Live Aid was a very odd thing to do, really. It was the old trap. It was like George Harrison was saying in Q recently that he always had to be careful in case Paul and Ringo were both invited to do the same show and it would be, Oh, as the three of you are all here, why don’t you get together and give us ‘Love Me Do’ or something? And that’s exactly what happened to us at Live Aid. I’d been asked and Jimmy had been asked to play separately and the emotional onus swung round to whether or not I’d eat my own words because I’d always said ‘No, I don’t want to play with them again. I just don’t want to rest on my own laurels for the sake of some glory that’s out of time.’ But there it was. I found myself saying, ‘Yeah, what a great idea, let’s have a rehearsal’ and we rehearsed with Tony Thompson and then Phil Collins came on his plane and we virtually ruined the whole thing because we sounded so awful. I was hoarse and couldn’t sing and Page was out of tune and couldn’t hear his guitar. But on the other hand it was a wondrous thing because it was a wing and a prayer gone wrong again – it was so much like a lot of Led Zeppelin gigs. Jonesy stood there serene as hell and the two drummers proved that…well, you know, that’s why Led Zeppelin didn’t carry on. But through all that and through the rejection of ever having anything to do with that song again, through facing all these compromises, I stood there smiling. The rush I got from that size of audience, I’d forgotten what it was like. I’d forgotten how much I missed it. And I’d forgotten how Led Zeppelin and Bonzo could never, ever be replaced. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t really drunk on the whole event. The fact that they were still chanting for us 15 minutes later and the fact that there were people crying all over the place…odd stuff. It was something far more powerful than words can convey…It’s just filled me up with tears thinking about the whole thing…”

By the time of Live Aid, Robert Plant had already recorded his first three solo albums (as well as The Honeydrippers‘ set, a collection of old rock ‘n’ roll standards featuring Page and Jeff Beck on guitars). It’s taken him another two and a half years to record his fourth (and best) and to get the spectre of Led Zeppelin finally out of his system. But can you ever truly lay the ghost of a Devil? Last night in Folkestone, Robert Plant found himself getting up to old tricks: “I don’t know where it came from, my style. I must have been pretty insecure when Zeppelin started to want to run around puffing my chest out and pursing my lips and throwing my hair back like some West Midlands giraffe. But I did it again last night. And when I did it, I laughed so much. It was like self-parody; I was wiggling around like some ageing big girl’s blouse and I realize how stupid it all looks. I mean, last night while I was crouching and leaping up in the air and doing a spiral as I came down again, I thought ‘I wonder if David Coverdale does that yet?’ But that’s what I’m good at. That’s what I know. What else am I going to do? Sleep with the board of directors of Coca Cola and make an ad? I don’t know. I don’t want to end up playing in the back room of some pub in Wolverhampton waiting for the night match at Molyneux to end. It’s a bit of a naff old game, life…”