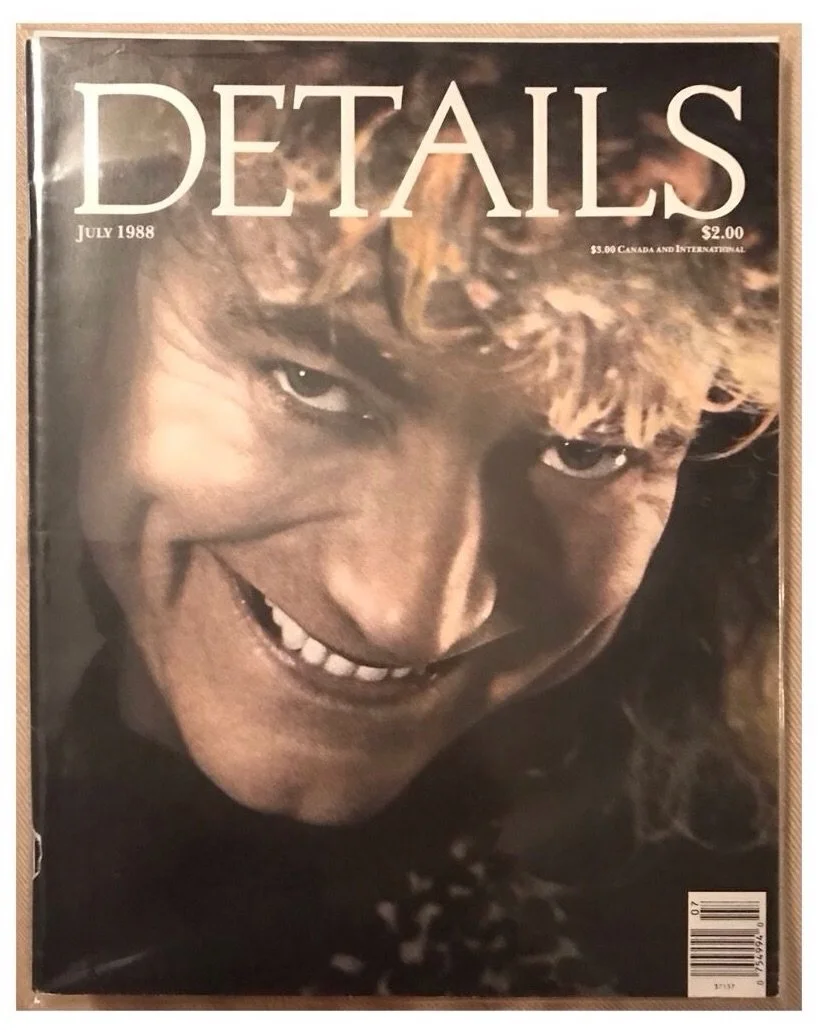

DETAILS Magazine - 07/1988

Interviewer: Danny Fields – Details Magazine, July 1988

“Well, don’t forget that the reason people dress up and become rock ‘n’roll stars is because I think we have something wrong with us anyway. We have something missing. Some kind of personality deficiency if you like, which we have to compensate for by being the centre of attention.” – Robert Plant, London, February, 1988

“EEEyaoww!! There’s no honey!” bellows the rock ’n ’roll star, seated on a glass coffee table in a crowded and cluttered office at Atlantic Records. It is the end of what has looked like, to the rest of us, a grueling photo session, and some nerves are on the verge of fraying. Not his – he’s enjoying being his own proverbial center of attention, and his Henry VIII honey-uproar was just to lighten up the atmosphere. “Maybe you didn’t stir it,” offers the helpful publicity person from behind her desk, where she’s trying to coordinate subsequent events in which the star will be involved. “I’ve probably been stirring my tea longer than you have, even,” he replies. “I know exactly what to do. There is nothing in here that resembles sweetness!” There is giggling, more advice, and a serious discussion about the possibility of finding any honey in this whole building at 75 Rockefeller Plaza. “Oh, it’s been a long day,” says Robert Plant with a grown-up smile that takes in the room. “A very long day.”

From the beginning to the end of the ’70s, Robert Plant sang in front of (and wrote the Iyrics for) Led Zeppelin, the biggest group in the world for the duration of the decade. He’d been discovered at the age of nineteen, singing in a band called Obbstweedle in Birmingham, England, where he was known as “The Wild Man of Blues From the Black Country,” the part of the Midlands under which lie huge coal beds. Plant’s discoverer was a sensational and glamorous London guitar genius named Jimmy Page, who had been in the trendsetting Yardbirds, owned the name since they’d broken up, and was starting a band called—and why not—the New Yardbirds. The pieces were put together by mid- ’68, and as the legend has it, after a tour of Scandinavia, the New Yardbirds – Page and Plant, with bassist John Paul Jones and Plant’s Birmingham buddy John “Bonzo” Bonham on drums found themselves to be so new that they needed another name, and came up with Lead Zeppelin (the ultimate source of which remains a matter of dispute), dropping the “a” in “Lead” to avoid mispronunciation.

In January 1969, their self-titled debut album with the iconic Hindenburg cover was released, and rock ‘n’ roll has never been the same. “In my opinion,” Geffen Records A&R chief John David Kalodner recently told Rolling Stone for a sidebar story on Led Zeppelin that accompanied a cover piece on Plant, “next to the Beatles they’re the most influential band in history.” Ironically, Led Zeppelin appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone only once, a shocking fact in light of the band’s enormous success during their eleven-year lifespan. Then again, Led Zeppelin had no relationship with the press (except for Lisa Robinson), who were, nearly to a man (ahem!) terrified of them. There were all those stories about sharks, guns, satanism and a thuggish and brutish management. Besides, it was easier to deem the Rolling Stones “The World’s Greatest Rock ‘n’ Roll Band” and go hang out backstage with Mick, Truman, Lee and Liza.

“It’s funny, we always used to moan because the Stones got all the publicity,” Plant said during a long talk that took place just before the coffee table photo shoot. “But the Stones have always had that. At the time, we used to sit back and go, ‘It’s terrible really, but then again, is it important, really? Do we have to say how many records we broke? Is it important that the Daily Express and The Times and The Guardian all know this? Or would it be better if they didn’t know anything at all?’ We thought the press were a bunch of turkeys, and they were. “But the Stones always came out on top. I guess there was some rivalry there. Because we always knew we were doing the business and they weren’t. We only thought it mattered half the time- when they were near us. Or when one of our roadies wanted to go to them because they had more cocaine than we had. Like a takeover bid. You know, it didn’t affect how you played. It didn’t affect the reaction on any given night. It’s just that the confrontations were always a bit twitchy. But everybody pretended it was okay. Something like young boys pretending they’re studs. Ten Paul Newmans in one room. It didn’t really matter, but it was good to wind up the situation for a bit of sport.”

The last years of Zeppelin were brutal for Plant. In 1977, his six-year-old son died suddenly of a respiratory virus while Robert was on tour in America. And in 1980, his beloved Bonzo died of an alcohol overdose, and that was the end of the band. Without its drummer, it existed no longer. “I didn’t say it should finish, you know,” Plant explained with not a little bitterness. “I didn’t say it should be over. I didn’t say it should end. It just ended.” That Robert Plant even talks about Led Zeppelin is a revolutionary development, because for years he refused to answer any questions about it whatsoever. Now, he not only talks about it, but talks about talking about it, and the process seems to be therapeutic. “It’s only recently that I’ve started even thinking of Led Zeppelin and what it was to me. And I realize what it’s done to me in every respect. But what it was to me is something quite clear. All those years, I pretended I didn’t know who Led Zeppelin was. ‘Cause everybody who’s lame would mention Led Zeppelin instantly in an interview. Especially in the beginning, when I started my solo career.”

Some background: When Led Zeppelin ended its run, Plant was rich enough to remain mythical for the rest of his life. It is likely that the thought never entered his mind. In 1981, he formed a band called the Honeydrippers, who got together to play the blues for fun, and had more than modest success. Also having more than modest success were Plant’s first three solo albums, described in his official bio as “adventurous and inventive,” and by himself as “my solo meanderings. . . this kind of wafting, aimless career I’ve had.” This year, in collaboration with keyboardist Phil Johnstone, Plant took aim. The result was the album Now and Zen, critically acclaimed, commercially extremely hot, and for its creator, satisfying at last—”What I’ve been looking for, for about seven or eight years, a kind of light-hearted freedom of spirit. I’m really quite pleased.”

But at the onset of the solo career, there was that old, gigantic shadow. It was hard to make progress on his own terms. “I had no kind of track record. Nothing at all, except once I was the king of cock rock, you know, and wrote a few songs about hobbits and stuff. And so when you start your solo career and everybody’s asking you, ‘Is it true about the Butter Queen?’ or something or other, I pretended I couldn’t remember, or said I’d gone to bed early and missed all that, or else I just couldn’t be bothered about it. And people were told, ‘Don’t ask him about the war, don’t mention the war or Led Zeppelin.’ And it was good, you know, because it allowed me psychologically to distance myself. It was almost a tonic, because I’d had an overdose of Led Zeppelin, however wonderful it really was. That wasn’t what I was going to tell anybody. I was there to say that this record, whatever solo album I was talking about, is the most important thing I’ve ever done in my life. Not give some old fart an excuse to write more dribble about Led Zeppelin. And now, because I’ve finally made one record that kind of carries on the tradition, sonically and intentionally, now I can talk about it again, and now I can sing those songs. Now I’ve stopped wallowing around.

“I can actually say I’m proud as hell of Led Zeppelin, and I can hold my head up. And after all that kind of ego rejection. It’s just that there was something rather grand about it, for all its kind of meanderings. It was a very kind of impromptu to accidental thing. If it happened, it happened, if it didn’t it didn’t. Whatever the outcome of it, it was always quite remarkable that we didn’t really ever go over old ground. And I’ve tried to do that since, and so in his own way has Page. We didn’t write ten ‘Kashmir’s or six hundred ‘Whole Lotta Love’s, because we were always busy doing something else then. Like recording in India with the Bombay Symphony Orchestra on tapes that never saw the light of day, but were hilarious. Because we took a bottle of brandy to the sessions, and the Indians went straight for it.”

There was, of course, a first Led Zeppelin reunion, and it took place at the huge Live Aid concert, in July of 1985, at Philadelphia’s RFK Stadium. Two drummers, Phil Collins and Tony Thompson, took the place of Bonzo, and to many there it seemed that this incarnation of Zeppelin was the great moment of the star-filled benefit, bringing all the various constituencies in the audience together. But what do the masses know? Robert Plant hated it. Hated it. “Live Aid was awful, I mean for us. We were awful. Live Aid was wonderful, let’s get it right. I was hoarse, I’d rehearsed all afternoon, I’d sung three concerts in succession with my own band at the time, and when I came to sing that night I had nothing left at all. Nothing there. And the whole Led Zeppelin saga returned to me instantly on that stage. What I hated about Led Zeppelin came right back. It was like some kind of aimless dog trying to bite its tail, that was the actual vibe on stage. The road manager handed Page his guitar and it was out of tune, because he hadn’t taken it out of the case even for about ten years. And the guitar leads weren’t long enough. He was staggering around. I was trying to get to the front of the stage. It was a joke. “The project had no balls then. It had seemed like a good idea, but the whole thing ran away with itself, and it was almost too much of an emotional thing for me, to stand there absorbing this kind of congratulations, when really I was on my way to Cleveland to do a solo gig. It was quite strange, and it was also a kind of defeat for me as an individual, as a solo performer. The day being the day it was, and it being such a special day, for me to stand there and do probably one of the worst performances I’ve ever done in my life seemed to contradict my very being, my reason to be, as an entertainer, as a musician. It was a most peculiar sensation. The idea of doing that every night is probably one of the least attractive things I could think of. Being in Cleveland the day afterwards with my own band was much more fun. Part of everybody’s past and present is what I was at Live Aid. Now I’m an artist competing alongside a lot of pretenders, and a lot of pretty decent musicians. And this is much more realistic.”

Robert Plant turns 40 this year, on good terms with his past, but much more interested in what he’s doing now, and, if anything, amused that his current audience on his ’88 American tour is half his age. “I just do what I do and they can come if they want to. I mean, the doors are open and people can come in. I don’t look down and think, ‘God, that could be my daughter!’ I don’t really think that age has got anything to do with it. It’s just enjoyment, really. I’m an entertainer. A very selfish one, but I’m an entertainer. It’s easy to get old. There’s nothing hard about getting old. It’s also hellishly inevitable. You just have to look at yourself and say, well, every dog has his day. And mine is today. “I think in Led Zeppelin I wasn’t quite as cocky as I am now. I mean, my success has diminished and my cockiness has risen. I just think that you do what you do and you get on with it, and there is no point in thinking too seriously about the whole issue. Obviously, I like success, but if I attempt too much to make it into a big meal and a big deal, then I’m gonna lose the point of it.”

The cockiness erupts every so often. Plant loves to hate the current crop of Zeppelin-influenced groups, especially the multimillion-selling Whitesnake and its big, long-blond-haired lead singer, David Coverdale. “He and I are very good friends. We go back so far we even left the womb at about the same time. And I think it’s wonderful and I’m really pleased that some old farts who weren’t going to get on anywhere in the world have found some kind of niche. And I know he’s furious that I say these things. I mean, a lot of these bands are much younger, and that’s okay, but when the guy is the same age and from the same stable, then I think discretion has to be called to order.”

And then there was this exchange about Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones, who was in New York at the same time as Plant, doing interviews on behalf of a band called The Mission U.K. whose album he’d produced:

Me: I interviewed John Paul Jones yesterday. He’s in town. Robert: Yes, hooking on 42nd Street where he belongs.

Me: And he’s promoting that nice group The Mission U.K. that he produced. And he’s helping them out, which is nice. Robert: Fabulous.

Me: I think it’s nice. Robert: I think it’s a very big gesture on his behalf. I mean, otherwise he’d be in Great Britain, in Devon, where it’s freezing cold and boring, with his wife. I think it’s really good of him to come here with The Mission U.K. playing Led Zeppelin outtakes.

Me: It is a good band. Robert: Bighearted of him.

When the camping ends, there’s a charming guy with a solo career that’s now going the way he wants it. How does he live? Well, he has a house in London, a new acquisition. “My daughter lives in one half of it with a door that doesn’t open in between so I can keep her away from me, and I like it. I like cities, but I like to run away as well. Anywhere. My diary for last year has pages and pages about the thrill of actually flying over North America. And my ambition is to drive it and walk it. I couldn’t really live anywhere for very long. I thought about going to a doctor about it, see what he says. He’d probably say if you can afford to go, keep going.”

The photo session ends. Robert Plant tells the photographer, “I feel rather demented. This was wonderful!” He asks me if I think he’ll enjoy Hairspray, which he’s off to see that evening with his new manager. I tell him I liked it a lot, and that it has a happy ending. “Good,” he says, “everything should have a happy ending.” Then he walks out of the room. Among those who stay behind, there’s a feeling that a round of applause wouldn’t be out of order.